Abstract

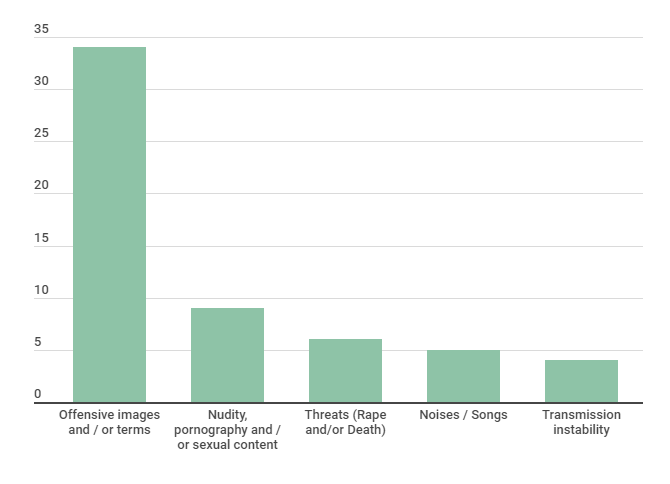

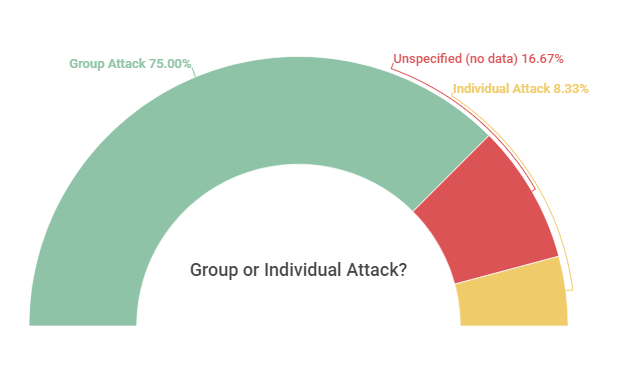

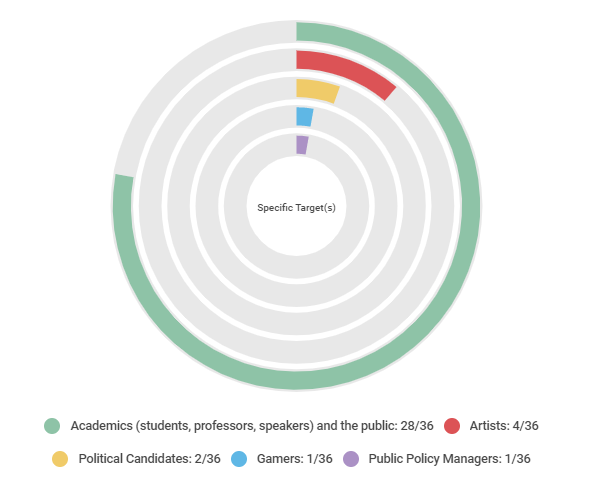

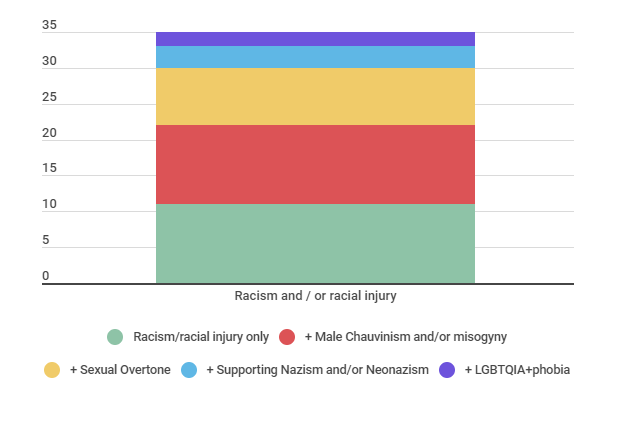

This article presents an overview of attacks and invasions of virtual events in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on a monitoring of cases that occurred between April 2020 and February 2021. Aiming to foster discussions on human rights violations and Internet anti-democracy through racism and racial injury, Male Chauvinism and misogyny, lgbtqia+phobia and other means of aggression and destabilizing the debate, a qualiquantitative content analysis of the information described in 36 documents from collected sources (institutional open letters, in news and articles and videos from portals of affected institutions) was carried out. The objective was also to identify the tactics, the means and types of attack, the most used platforms, the genres of the most affected event and understand if the aggressors acted in groups. It was concluded, in general terms, that the most recurrent attacks, in decreasing order, involved racism and/or racial injury, Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny, sexual connotation, apology for Nazism and/or neo-Nazism and LGBTQIA+phobia. In addition, the most recurrent medium was the use of offensive images and / or terms, including Nazi symbols and images; nudity, pornography and sexual content; rape and death threats; noises and music; and provoking instabilities in transmissions. Google Meet was the most used platform, the month with the most attacks was July 2020 and 14% of the cases mentioned President Bolsonaro. The majority involved more than one category concomitantly (racism and/or racial injury and Male Chauvinism and/or misogyny, for example), and 75% of the cases involved group attacks.

1.Introduction

Throughout the covid-19 pandemic, there was an increase of 5000% in hate crimes, child pornography and neo-Nazism in the main social networks (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, in addition to some anonymous user chats, channels and forums), according to a study by SaferNet Brasil, which had its results republished by Intercept in August 2020 (Dias, 2020). The analysis, which used data from the National Crime Reporting Center, covered cases received in 2019 and 2020, comparing the situations in the two years, especially considering that, in 2020, the pandemic, circulation restrictions and other measures in favor of social isolation had started in Brazil.

However, little research and news has been carried out to identify, with greater precision, how hate crimes and other related illicit acts have occurred on platforms for streaming virtual events, whether academic, electoral or entertainment. Even news portals have identified that attacks in these categories have occurred frequently throughout the pandemic (Universa, 2020; Folha, 2020; Godoy, 2020; Casaletti, 2020; Moura, 2020).

In order to fill this gap in productions aimed at a careful analysis of these attack tactics, a monitoring of institutional open letters, journalistic news, articles and videos on portals of the affected institutions was prepared for the writing of this scientific article on cases of aggression, hate speech and methods of destabilizing the debate, with each situation being allocated to one of the categories created (racism and / or racial injury; Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny; sexual connotation; apology for Nazism and / or neo-Nazism; and LGBTQIA + phobia), as will be described in section 2 (Methodology) below.

However, the collection and analysis of these secondary sources alone does not provide sufficient elements for a more complete observation of the whole issue and how the scenario has worsened. To complement the study, it was also necessary to find out what other authors have already been writing about security and human rights on the internet during the pandemic, as presented in section 3 (“Pandemic and internet: the scenario”).

A continuation of this literature review also allowed the introduction of already existing concepts about the methods of aggression and invasions to such virtual seminars – such as the term “Zoombombing”, which was better described in section 4 (“Invasions and / or attacks: identifying strategies to destabilize the debate ”).

As for the data actually collected in the monitoring, all started to be worked on in section 5 (“How were the attacks?”), which, as the title already says, aimed to outline, through the categories created and the analyzed sources, a panorama of which were the most used methods, and if the aggressors acted in groups or in isolation, in individual attacks.

In section 6 (“What type of occurrence is the most common in the attacks analyzed?”), the results of categorizing and counting the frequency of cases by gender of attack were presented – such as racism and / or racial injury, LGBTQIA + phobia and other types highlighted in the Methodology section. However, it was also necessary to resort, again, to the literature review to understand the ways and the reasons for different categories to intersect with others: here, the concept of “intersectionality” elaborated by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) was used in her paper “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics”, published by the Legal Forum of the University of Chicago.

In that paper, the analysis of the situation of black women, especially Americans, led the author to an observation that the violence and inequalities to which these women are subjected are related not only to their race / color, but also to their gender, class, ethnicity and other possible variables (Crenshaw, 1989). In a similar and complementary way, another Afro-American scientist, Patricia Hills Collins (2000), understands that the cultural patterns of oppression, while structural aspects, also intersect and are related to each other.

These authors were recovered in this article and in section 6 because they help to understand why, according to the results that will be presented in that section and in its subsections, cases of invasions and attacks during virtual events often refer to situations of “racism and / or racial insult ”(spelled out here in quotation marks, as it was a category created for codification) and “Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny ”(in quotation marks for the same reason) at the same time, for example – causing black women to be hit twice, as well as black LGBTQIA + women. It is worth mentioning, here, just as an example, a case that emerged during the finalization of the writing of this article and that, given the time frame of case collection that occurred until February 2021, it was not possible to include it in the monitoring, but it is worth mentioning: according to an article published by Portal Uol (Lopes, 2021), the veterinarian Talita Santos suffered a racist attack during a virtual lecture. She was returning to a study group at Unesp in Botucatu, when a user opened his microphone to curse and transmit a lot of loud noises. Shortly thereafter, the scientist was informed that a “collective invasion” was taking place, with other users broadcasting their screens and projecting sounds and images of primates and the current President of the Republic, Jair Bolsonaro.

In section 7 (“Where?”), the results of which types of events had the greatest number of cases will be displayed, as well as which platforms and software are most used for transmission. Section 8 presents which sources mention who were the most specific targets, in addition to all the other participants – university professors, congressmen/ congresswomen, players, electoral candidates and others. In section 9 (“When?”), in turn, graphs will be shown reflecting the periods with the most cases collected, within the time frame used. And, in section 10 (“Inside the sources”), the documents used as sources will be addressed, in order to understand whether the amount of disapproval notes from the institutions promoting the events was equal to or greater than the amount of journalistic news found, seeking, in addition to complementing the topics covered in the Methodology section, to identify how the debate has emerged in civil society and which mechanisms and spaces for reaction have been adopted.

Finally, in the Final Considerations, all the central results will be presented, mainly answering the questions that this article aims to answer and that is present, as described, in each section and subsection – how, which, where, against whom and when such attacks and invasions occurred?

2.Methodology

For this article, mostly qualitative methodologies were used, although the content analysis employed is qualitative and quantitative because it considers, in addition to the categories and codifications created to observe the qualitative data, the frequency or the number of appearances of each of them, allowing the generation of graphs with percentages and gross numbers of cases by type.

In addition to the bibliographic review, mainly qualitative data were also collected up to February 2021 – news in the media, open letters and articles on portals of host institutions that had cases of invasion and / or racist, sexist, lgbtqia + phobic and other related attacks to the participants of lives, online classes and virtual congresses. In total, 36 cases were identified, with 28 documents (news, notes etc.), always prioritizing the collection initially of institutional open letters and, in their absence, journalistic articles on the subject and, finally, articles or videos on portals, and news reports from the affected institutions, respecting the limit of only one document per case, since the objective was not to understand how the same case was reflected in different sources, but to collect qualitative information about each case.

In order to have access to this data, Google alerts (Google Alerts) and searches in the same search engine were elaborated with the following keywords, in Portuguese, usually associated: “open letter”, “online class”, “racism”, “Male Chauvinism”, “Misogyny”, “homophobia”, “LGBT”, “invasions”, “attacks”, “live”, “meeting”, “congresses”, “academic congresses”. The links found were allocated to a spreadsheet with institution, month and year of occurrence, and the PDF documents from the links were also stored for analysis in the Atlas.ti software.

Both in the spreadsheet and in the indicated software, categories were created to list each available case in a link (in some situations, the same open letter, news or article refers to more than one case, and each was categorized separately, preserving it if only its common source) to one (or more) type (s) of attacks and / or invasions occurring involving: 1. racism and / or racial injury; 2. Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny; 3. Nazism; 4. LGBTQIA + phobia; 5. sexual connotation.

Therefore, the variables used were the location (university, group etc.), the target (s), the institution where the case occurred, the year, the month, access link to the source document, type of document, type (s) of occurrence, whether there was mention of President Bolsonaro (Boolean or binary variable, which can be set to 0 to indicate that there was no mention, and 1 to indicate that there was mention based on the search for the word “Bolsonaro”, according to the reports in the documents used – in the event that such information does not exist in the sources, it was decided to register “N / A”), platform used for broadcasting the event (Zoom, Hangouts, Google Meet etc.), event privacy setting (if fully open, if it was open but depended on prior registration or if it was restricted ), whether the performance was in group or an individual attack and the method (s) of attack (such as the transmission of noise and music, offensive language, etc., as will be described in the following paragraphs). The categories created for each variable are indicated in the following table:

| Variable | Category 01 | Cat. 02 | Cat. 03 | Cat. 04 | Cat. 05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place/Event Type | Academic Event | Electoral Streaming | Game Streaming | Artistic Streaming | PP Managers Meeting |

| Target(s) | Academics and the Public | Political Candidates | Gamers | Artists | PP Managers |

| Institution | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY |

| Year | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY |

| Month | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY |

| Link (Source) | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY | NO CATEGORY |

| Source Type | NEWS IN MEDIA / PRESS | OPEN LETTER | NEWS / ARTICLES ON INSTITUTIONAL PORTALS | – | – |

| Occurrence Type | Racism and/or racial injury | Male Chauvinism and / or Misogyny | LGBTQIA+phobia | Supporting Nazism and/or Neonazism | Sexual Overtone |

| Mentions Bolsonaro? | 0 (NO) | 1 (YES) | NO DATA | – | – |

| Platform | ZOOM | YOUTUBE | GOOGLE MEETS | UNSPECIFIED | |

| Privacy Settings | 100% OPEN | OPEN W/REGIST. | PRIVATE | – | – |

| Group or individual attack? | Group Attack | Individual Attack | NO DATA | – | – |

| Attack Methods | Offensive images and / or terms | Nudity, pornography and / or sexual content | Threats (Rape and/or Death) | Noises / Songs | Transmission instability |

To categorize a particular case in a type of occurrence as racism and / or racial injury, source documents were analyzed looking for the very terms “racism”, “racist”, “racial” or “race”, but also reading and understanding whether the case involved racism, albeit in other words – for example, there was an explicit mention of the racist lines of attackers, such as “monkey”, but there was no explicit mention of the term racism in the document. The same method was applied to the categories Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny, looking for “Male Chauvinism”, “misogyny” and related words, and to the categories LGBTQIA + phobia (searching for “homophobia”, “transphobia”, “lesbofobia”, “LGBTQIA +” , “LGBT”), nazism (with the very clear terms “neo-nazism”, “neo-nazis”, “nazism” and “nazis”) and sexual connotations (“nudity”, “sex”, “sexual”, “porn”, “ pornography ”and“ mutilation ”).

Furthermore, aiming to categorize the method (s) of attack adopted, it was observed, in the sources, whether the case descriptions involved offenses, noises to interrupt the speakers, presence of many users simultaneously, threats, instabilities, projection of aggressive and nudity images, as well as if the medium was an invasion and / or attack. In addition, it also sought to identify in which and how many those involved made reference to President Jair Bolsonaro. This was not an isolated action and it was precisely similar to cases that appeared frequently among those collected during this work.

Finally, the variables that not categorized were those that did not need to create codes since the values found in the documents are, by themselves, sufficient to explain its content (such as month and year of occurrence and publication of notes, news and articles, as well as access links).

3.Pandemic and internet: the scenario

During the covid-19 pandemic and the resulting social isolation, many different types of cyber-attacks began to happen with even more intensity and frequency.

As Mouton and De Coning (2020) found, phishing attacks (such as emails sent in the US about alleged tax refunds that could provide financial relief to citizens during the pandemic but which, in fact, were a scheme to collect bank and personal data), fake URLs (scammers that redirected users to malicious website addresses, usually about campaigns against covid), fake donation sites for families in socioeconomic vulnerability, misinformation about covid-19 and other tactics have become increasingly popular in this period.

In addition, for Khan, Brohi and Zaman (2020), mobile applications, malicious messages on social networks, websites and domains, DDoS attacks and other types of aggressive media content? have also intensified and were considered major threats to cybersecurity in the midst of the pandemic.

However, both in Brazil and abroad, little was said about invasions and / or attacks directed at the lives of academics and artists – and, in particular, those that promoted debates on agendas considered progressive, such as anti-racism, feminism, environmental preservation, deinstitutionalization of the Military Police or criticism, in some way, of the Federal Government, as Godoy (2020) observes in an article published by Estadão. The author also observed how these attacks occur, especially those that use “zoombombing” (a technique that will be better explained in the following section) to destabilize or make the debate unfeasible.

4.Invasions and / or attacks: identifying strategies to destabilize the debate

4.1.Invasions

Both before and during the pandemic, invasions of private online rooms, usually subject, in the case of open events, to prior registration to receive links and passwords, have become a common phenomenon on the Internet.

In these cases, what happens is usually either, in fact, an invasion attack due to cryptographic breaches and a failure in the security of the platform, or the supply of false and / or third party data for the requested prior registration, as occurred in the case of one of the events analyzed in the monitoring – the MaRIas seminar, organized by the feminist collective of the Institute of International Relations of the University of São Paulo, during 2020, in which malicious users made their registration using data from students and professors of that institution, so that they could go “unnoticed” when accessing and following the discussion.

The problem with these intrusions is that, in addition to the exposure of the participants and being a serious breach of privacy, “intrusive” users also tend to promote a series of attacks that will be better described in the following subsection. And, even when the conference rooms and online events are totally open and public, although it is more difficult to argue for an “invasion”, what happens is the massive presence of large groups of users who, united in favor of destabilizing the debate, begin to attack speakers. Increasingly common on the Zoom platform, this type of attack was called “Zoombombing”, favoring what researcher Sarah Young calls a true “privacy crisis” (Young, 2020).

4.2.Attacks

Zoombombing, despite its name, is not restricted to Zoom. On the contrary: it is just a new name given to a phenomenon that is already very old on the Internet and that has existed for longer than the platform mentioned, being also recurrent in virtual events and other types of streaming such as Youtube, Twitch, Google Meet, Hangouts, Discord and other apps.

Among the possible attacks that can occur within this modality, are: 1. speaking over the speakers and / or presenters, preferably in large groups, so that it is not possible to hear them, or even make noises, insert music and videos in high volume for the same purpose; 2. turn on the camera and / or present the screen to display pornography, nudity and other explicit images to participants; 3. offend by text over the broadcast chat, by voice, video and / or other types of offensive images; 4. threaten (from death, rape, disclosure of personal data or any other type of threat); 5. promote instabilities in transmission, either through a really invasive attack via hacking or by other means that do not involve invasion, such as calling many users to make the connection unstable.

Such behaviors, generally used during the attacks studied here, are very common in three types (concurrently or not) of users: “fakes” (false profiles of people), “trolls” and “haters” – the latter two, according to Kalil (2018), have aggressive and disproportionate attitudes, in addition to making use of jokes and offenses to provoke the destabilization of the debate or reproduce hatred free of charge, but haters tend to reproduce more hate speech and have more aggressive behaviors than trolls, whose speeches are more based on “pranks”, “traps” or “jokes”. Still for the author, in the 2018 presidential campaigns in Brazil there was an expressive number of users of this category among the current president Jair Bolsonaro’s supporters. It is worth noting, then, that, in at least 14% of the cases observed in this article, there was an explicit mention, by the attackers, of the aforementioned president.

5.How were the attacks?

In the cases analyzed during the monitoring, the use of images and / or offensive terms during online events was the most recurrent method (Graph 1 below), followed by nudity (own or pornography) or sexual content, threats, noises and instabilities in the streaming.

As for the first category, messages related to different types of occurrences are highlighted, which will be addressed in the following section – racism and / or racial injury, Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny and others. Offenses such as “THERE ARE SO MANY POORS HERE! UGHH, BLACK PEOPLE!” – received during the IFPR virtual seminar (Moura, 2020) -, “stop talking, you blacks” – speech given during a meeting of the State Council for Human Rights of Santa Catarina ( Caldas, 2020), “Preto = Macaco” – message displayed at the IFTO seminar (IFTO, 2020) -, in addition to offensive images – such as Nazi symbols and references displayed during an event from Revista África e Africanidades (Correio do Amanhã, 2020) , in a meeting on anti-racist practices promoted by Icom – Instituto Comunitário Grande Florianópolis (Senra, 2020) and in lives of other institutions – were extremely recurring.

In terms of “nudity, pornography and / or sexual content”, which appears in second place and includes both nudity itself, as well as pornography and sexual language, the following stand out: the Icom seminar, with images of a man masturbating (Senra, 2020); the IFPR event, with pornography and genital mutilation (Moura, 2020); a live from Ifes, which was the target of pornographic images and threats to participants (Sinasefe Ifes, 2020); a NEABI seminar, which also had to deal with the display of pornographic videos (Amorim, 2020); in addition to other events.

Threats of rape and death were also frequent. Here, it is possible to highlight the following cases of virtual events promoted by the following institutions and people: IFTO (2020); Ana Lucia Martins, elected councilor of the PT and black woman (Estadão Content; IstoÉ, 2020); a seminar for teachers and students from an unidentified public school in Belém (O Liberal, 2020); IFPR (Moura, 2020); Ifes (Sinasefe Ifes, 2020); and UFSM (2020).

The fourth tactic (inserting music at high volume or making noise to destabilize the debate or prevent speakers from being heard) is a relatively common strategy in cases of zoombombing, as presented in the previous section. In the cases analyzed, although it was one of the least recurring means, this mode of attack reached lives and hindered the oral presentation of an event promoted by Unicamp (2020) – while the speakers were talking, several users simultaneously opened their microphones and spoke over them – , from a meeting promoted by the Gender and International Relations Study Group of IRI / USP (MaRIas, 2020) – with screams and loud music -, from an Ifes event already mentioned (Sinasefe Ifes, 2020), from a seminar promoted by UNB Institute of International Relations (Estadão Content; Carta Capital, 2020) and many other virtual events.

In the last position, there is the least used method and the one that perhaps requires more technical knowledge to cause problems: the provocation of instabilities in the transmission of events. Unless the platform used does not support or optimize a large number of users connected simultaneously, the only means of causing instability in streaming, and not just in the debate, depend on a more specialized knowledge about invasion techniques, repetition attacks and other related means. The few cases in which this category was mentioned were the artistic lives of singer Teresa Cristina (O Globo; Yahoo, 2020) and actress Maria Zilda Bethlem (Casaletti, 2020). The live situation promoted by Ineac (Estadão Content; Carta Capital, 2020) which, although it did not necessarily imply instability, was also allocated to this category due to the massive amount of “dislikes” attributed to the transmission on Youtube and to the attempts, by the management of the event, of interrupting and resuming the recording so that the attackers stopped, which had no effect and ended up generating instabilities and interruptions for those who were watching.

Additionally, it is also worth noting that, as shown in Graph 2 below, most of the attacks, among those that the documents (sources) provided information about, were carried out in groups, and not with just one user acting in isolation. This is extremely important information, because understanding how these users act is also understanding how to prevent invasions and aggressions, especially when it is possible to perceive, depending on the platform used, when many users are entering a transmission at the same time. In addition, it is possible to inquire about the other platforms that these groups use to communicate, integrate and plan attacks together – anonymous user chats and forums, Discord, Twitch and WhatsApp might be some options, although it is not possible to verify this in this study.

Finally, it is essential to mention that, for hate speech researchers on the Internet, different types of users with different strategies and motivations exist and there is no single answer for what would be the profile of individuals who practice such actions. In an analysis of Islamophobia cases, especially on Twitter, Awan (2014) identified at least 8 classifications that were later redeemed – during the pandemic, including – by Rudnicki and Steiger (2020: 14): 1. “travelers” – those who visit Twitter specifically to harass Muslims; 2. “apprentices” – new users who are guided by more experienced attackers; 3. “disseminators” – those who share and spread Islamophobic memes and images; 4. “impersonators” – fake accounts and profiles made just to spread hatred; 5. “accessories” – people who join the conversations of other people and groups to target specific targets, especially vulnerable individuals; 6. “reactives” – people who start practicing hate speech online after a major violent incident, such as a terrorist attack; 7. “movers” – users who are frequently banned and need to migrate from account to account to continue attacking; 8. “professionals” – individuals with a large number of followers and who initiate campaigns against Muslims.

6.What type of occurrence was the most common amongst the attacks analyzed?

In the cases analyzed, as shown in Graph 3 below, the category “racism and / or racial injury” stood out, with 28 occurrences (in 36 cases collected) related to the theme, especially against black people (in 27 of the 28 occurrences and, in one of these, with an attack also directed at indigenous people). In a last case of racial injury, there were attacks exclusively against yellow Asian people. Subsection 6.1 seeks to present the intersectionality of the themes of this type of category (Graph 4) and the corresponding literature review on the subject.

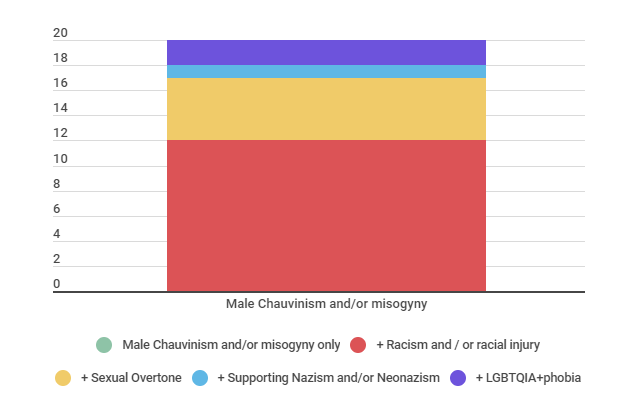

The second most frequent occurrence was “Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny”, present in 14 of the 36 cases collected, as shown in Graph 3 above. In subsection 6.2, we seek to understand how such attacks have been increasingly recurrent in the networks, especially during election campaigns and against female candidates. In addition, another graph (5) shown in the subsection shows how the intersectionality of cases occurs – for example: in 12 of the 14 total (approximately 86% of them), this category was associated with at least cases of “racism and/or racial injury”, of the first type of occurrence covered in this section.

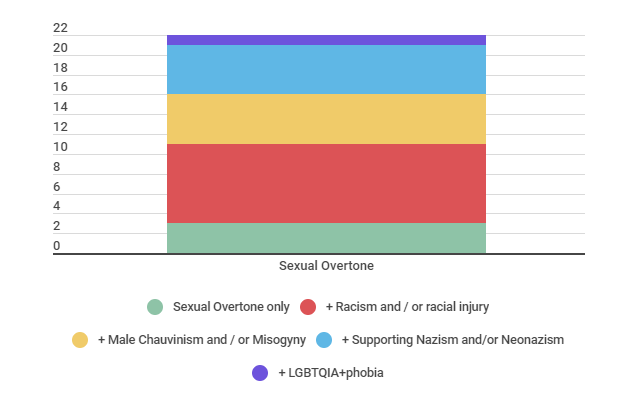

Occurrences involving the category “sexual connotation” were present in 13 of the 36 cases, occupying the third place in terms of frequency, according to the same chart above. As discussed in Graph 6 and in subsection 6.3. then, in most cases (8), such behaviors were directed at black people. In 5 cases, they were directed at women. In 4 situations, this category was associated with cases of Nazi and / or neo-Nazi attacks. And in one case, this was targeted at LGBTQIA + people. It should be noted that these numbers, added together, exceed 13 cases categorized in this way, as this type of occurrence was usually present in cases involving Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny, racism and / or racial injury, at the same time. However, it is also important to note that in 3 cases this type of occurrence occurred alone, without any association with racist, misogynistic, Nazi or LGBTQIA + phobic attacks, being, at the same time, the means of destabilizing the debate (addressed in section 5, in the category “nudity, pornography and / or sexual content”) and the type of occurrence (addressed in this section 6 by the code “sexual connotation”).

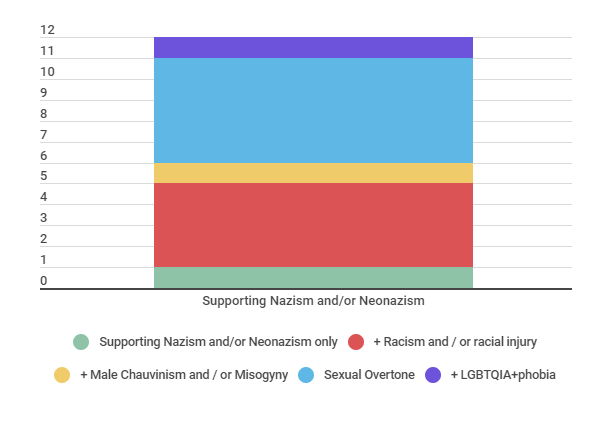

In the penultimate position are the cases of “Nazism and / or neo-Nazism”, in which 7 situations involved this category, as shown in the same Graph 3 above. In subsection 6.4. next (and in Graph 7), it was noticed that in 5 cases there was the concomitant use of attacks that are in the “sexual connotation” category. In 4 of them, there was also mention of the category “racism and / or racial injury”. And in two, ” Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny” was also present. Only in one case of Nazism and / or neo-Nazism, related images were presented, without any type of attack directly associated with the other types, and only in one case was there a direct attack on LGBTQIA + people.

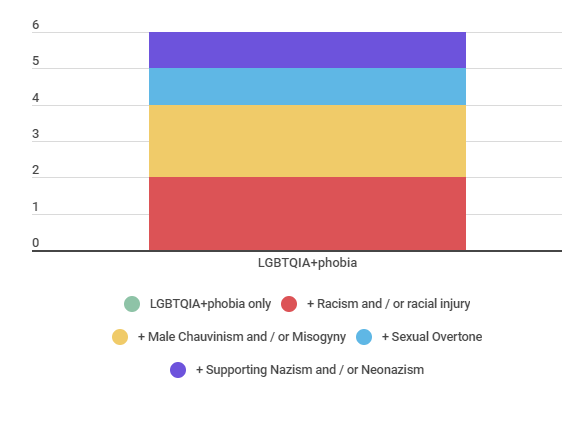

Finally, there are the events categorized as “LGBTQIA + phobia” (Graph 3), which total 4 related cases. As shown in Graph 8 and in subsection 6.5. then, half (2) of them was associated with the category “Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny”, and the other half (2) was associated with the category “racism and / or racial injury”. One of them also involved the use of the “sexual connotation” type of occurrence.

What these data reveal is that there is a clear intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) between the types of occurrences: almost never, the category “Nazism and / or neo-Nazism”, for example, appeared alone, isolated from the others. Especially because the ideology itself already presupposes an attack on the other vulnerable groups addressed here, especially directed at black people. And this is not only true for the category “Nazism and / or neo-Nazism”, but also for all the others, as demonstrated just above. Next, in the subsections on each topic, the graphs corresponding to the categories of type of occurrence created will be presented, and it will be possible to associate such alarming results with the existing scientific literature on the subject.

6.1.Racism and / or racial injury

From Graph 3 above and Graph 4 below, it is possible to see that racism and / or racial injury was the most frequent category among those created for the analysis of cases, and that the intersectionality of this theme with the others, specially Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny, was also recurrent.

According to Keum and Miller (2018), several factors can influence these and other racist behaviors and expressions on the Internet, such as online disinhibition, anonymity, de-individualization, prejudice rooted within groups, as well as their polarization, harmful attitudes external to the group and stereotyping. In addition, as Suler had already demonstrated (2004), this virtual disinhibition also leads to other forms of anger, toxic attacks and threats that, in theory, would be less present in life outside the Internet.

However, when talking about racism and racial injury today, and even about other topics mentioned in the following subsections, it can no longer be said with such conviction that these behaviors are less present in offline life. What happens, in fact, is that such attitudes can be more veiled outside the networks, but even this is not entirely true in the face of cases of constant violations derived from institutional and structural racism that, in Brazil, affect mainly black people both in access to the health system, such as education, basic sanitation, politics and other sectors (Lima et al, 2020).

6.2.Male chauvinism and/or misogyny

Graph 3 indicates that the category “Male Chauvinism and / or misogyny” was the second most recurrent in the cases analyzed, while graph 5 above reveals that it was strongly associated with other themes, especially racism and / or racial injury.

According to Ging and Siapera (2018: 520), this type of online attack allows women to stop expressing their opinions on the networks on certain topics – and, about this, the authors refer to a study by Amnesty International, published in 2017, about 32% of the women participating in the research have experienced this (Amnesty, 2017).

And this was not a dated phenomenon: also in 2020, during Brazilian municipal electoral campaigns, hate speeches against female candidates were so frequent that they inspired initiatives such as MonitorA, promoted by InternetLab itself and by the AzMina Institute, through the project Recognize, Resist and Remedy, in partnership with IT for Change and funded by the International Development Research Center (InternetLab, 2020). The intention was precisely to collect and analyze related cases on social networks.

What the present article is able to demonstrate, through the graphics displayed and the monitoring carried out, is that, in fact, women were much more exposed to these types of attacks, and that two of the cases collected (but that certainly were not the only ones in the total number of existing complaints, however they were those that the survey was able to collect with the parameters used) involved aggression against female and black candidates during lives promoted in electoral campaigns: Renata Souza, from PSOL (iG Último Segundo, 2020), and Ana Lucia Martins, from PT (Estadão Content; IstoÉ, 2020), the Worker’s Party in Brazil. This finding further reinforces Crenshaw’s (1989) arguments about intersectionality and dilemmas arising from different variables (race / color, ethnicity, gender, class…) when it comes to the experience of black women in all spheres.

6.3.Sexual overtones

In this category, all cases involving sexual connotation were allocated, whether the victims were women, black people, LGBTQIA + or belonging to any other social group. In addition to being the third code with the highest number of results in relation to the types of attacks (see Graph 3), a similar code was also created in terms of attack methods, in section 5, in which this was the second means of destabilizing the debate and attack the speakers and the public. As Graph 6 above reveals, it is also possible to see that this category has been recurrently associated with racism and / or racial injury.

An article published in The Guardian in April 2020 (Batty, 2020) indicated that, in the United States, “Zoombombing” attacks using the projection of “extreme” pornography during seminars and virtual classes became increasingly common. Considering that April was still the beginning of the pandemic, even in the USA, this data is even more alarming, as it reveals that this has been a concern since the beginning of emergency remote education and digital alternatives for face-to-face events.

6.4.Apology to Nazism and / or neo-Nazism

Meeting and complementing the aforementioned study by the organization SaferNet Brasil, with results republished by Intercept (Dias, 2020), the data obtained by the monitoring that originated this article also reveals, as shown in Graph 3, that Supporting Nazism and / or neo-Nazism in the Internet has been a recurring crime and has increased not only on the platforms that SaferNet Brasil’s analysis with data from the National Crime Reporting Center has revealed (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, anonymous user channels and forums, etc.), but also on the virtual events analyzed here, transmitted via Youtube, Hangouts, Google Meet, Zoom etc.

Graph 7 above provides even more details, and with it is possible to see that this category was often associated with sexual overtone and racism and / or racial injury. Such information proves to be especially important because, in general, speeches related to Nazism and neo-Nazism tend to affect various social minority groups, configuring itself as a series of violations of several human rights at the same time, including many that were not found explicitly in the analyzed documents and that, therefore, were not categorized, but that can happen on the Internet as a result of supporting these “ideals”: empowerment and discrimination against people with disabilities, xenophobia, religious of certain congregations and many other themes, commonly in a concomitant way.

A recent article published by Deutsche Welle (Schuster, 2021), still in February 2021, reveals that the covid-19 pandemic, the social isolation and the remote education resulting from it have made it easier for teenagers to become easier targets for extremist groups, including Nazis and neo-Nazis, an evidence that is also shared as an opinion by many teachers of these young people.

6.5.LGBTQIA + phobia

Finally, as shown in Graph 3, the LGBTQIA + phobia category was responsible for the smallest number of cases, among those collected and coded in the monitoring. However, it also has intersectional characteristics, having appeared frequently in situations involving racism and / or racial injury and male chauvinism and / or misogyny, as indicated by Graph 8 above.

It is important to note that, as a study by the University of Colorado demonstrated with results republished by UOL’s Tilt portal (Alves, 2021), algorithms tend to make more mistakes and injustices not only with black people, but also with trans people. In addition, an article published by Coding Rights (Guedes, 2021), in Brazil, also identified something similar when it comes to facial recognition and its intersections between gender, race and territory. It is certain, therefore, that many technological tools, programmed by humans, tend to reproduce inequalities and prejudices.

However, when talking about attacks and invasions that were actually caused by humans in digital media, it is possible to be even more sure about how exposed trans people are on the Internet. And not just them: lesbians, gays, queers and all other LGBTQIA + minorities also end up being affected by speeches that, like those found in the analyzed documents, reinforce stereotypes and aggressions of the type. Three out of the four events that had such occurrences dealt, at the time of transmission, with the situation of trans women, including participants who were transsexuals. Another event, with black intellectuals, suffered attacks of a homophobic and racist nature, again reiterating how hardly such categories are found in isolation.

7.Where?

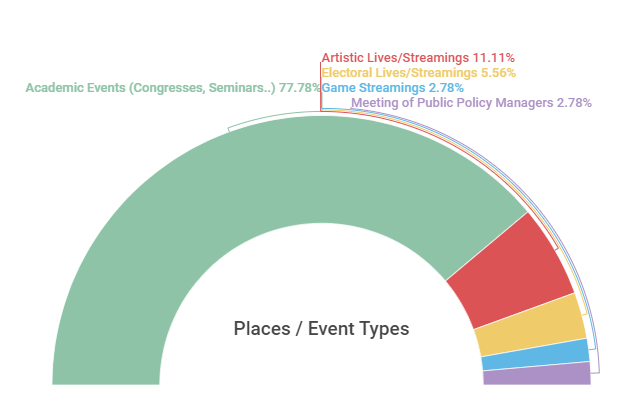

As can be seen in Graph 9 below, the highest percentage of cases analyzed (77.78%) occurred within the scope of virtual academic and scientific events, such as congresses, seminars, symposia, debates, meetings, workshops, lectures and the like, generally open to the public (with or without prior registration, link and password made available, and in some of them, the receipt of this data for access depended on the confirmation of your registration).

Lives and other means of virtual presentations promoted by artists and presenters made up the second place among the types of most frequent events in the observed cases. Among them, we highlight the attacks (offensive and / or aimed at promoting the instability of broadcasts) directed at singers Ludmilla (Folha, 2020) and Teresa Cristina (Casaletti, 2020), at the doctor, influencer and winner of the last edition of the relaty show Big Brother Brasil Thelma Assis (Universa, 2020) and actress Maria Zilda Bethlem (Casaletti, 2020), all women and who, except the last, are also black

What the graph above also reveals is that the electoral lives (promoted by candidates), although not very recurrent in the monitoring / clipping results, also represented 5.56% of the cases analyzed. Game streams, which are more addressed in other studies (Bertolozzi, 2021), also had little return (2.78%) using the research parameters for collecting cases described in the Methodology. This does not necessarily indicate that there were fewer cases on the platforms used for such transmissions (such as Twitch and Youtube), but rather a possible methodological limitation of the key-words used in the data collection, favoring a greater occurrence of attacks on academic lives. Finally, there was also only one meeting of public policymakers (representing 2.78% of cases) that was not allocated either to the reality of an academic event, nor to the situation of an electoral live, but which discussed agendas considered “Progressive” and aimed at guaranteeing human rights.

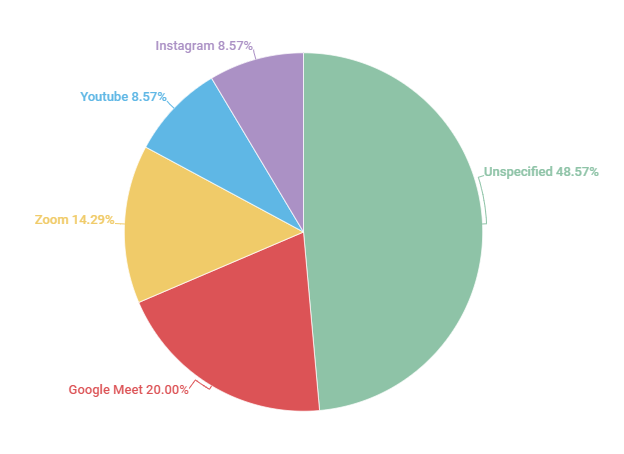

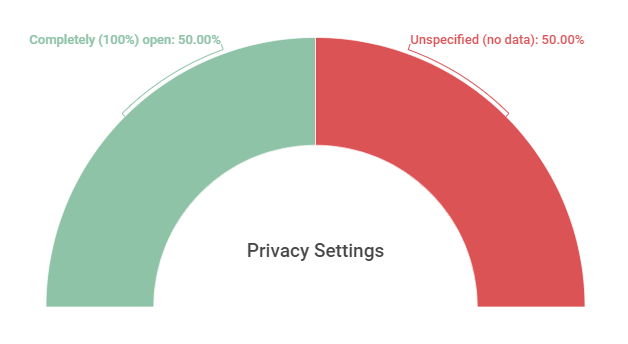

Finally, it was also possible to verify, as shown in Graph 10 and Graph 11 below, that most of the events mentioned in the documents were transmitted by Google Meet platform, and that almost all, among which such information was available, were completely (100%) open, even without the need for prior registration. Such information is also important to 1. question what is the responsibility of these platforms and how they can act to mitigate such cases – for example, by improving security and encryption guidelines, or by creating chatbots capable of detecting hate messages or screen projections with offensive content; and 2. identify how the privacy settings of these events are and look for alternatives so that public and open to society activities do not become private just for fear that attacks like this will continue to occur. Restricting access cannot be the only “solution”, although it is often the most widely used emergency resource. Concluding that fully open events are the most recurrent among those affected is also identifying a correlation – not a causality – and, being able to devise strategies to avoid future attacks.

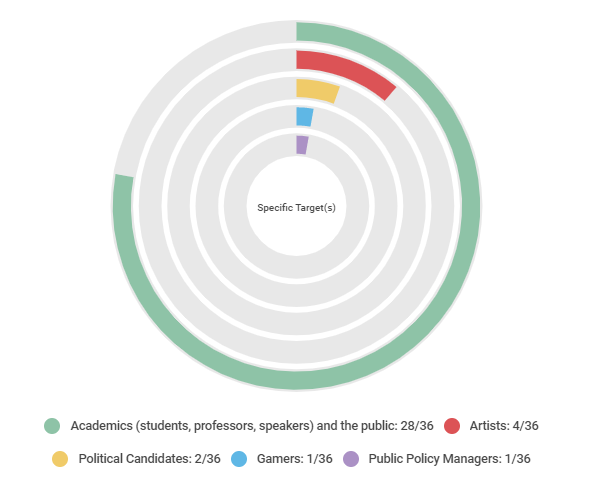

8.Against whom? Artists, congressmen, players, candidates, students, teachers ...?

In addition to targeting the public itself – and, here, it is impossible to categorize each individual, especially considering that many of these events are open to all communities – some specific targets were identified during transmissions and attacks, considering what had been described in the open letters, articles and journalistic news, and the different modalities of virtual events.

Graph 12 below indicates that most of the targets were concentrated on academics (students, teachers, researchers, speakers, etc.) – the “academic events” modality was more recurrent -, followed by artists, candidates, players and advisers or policy makers.

9.When?

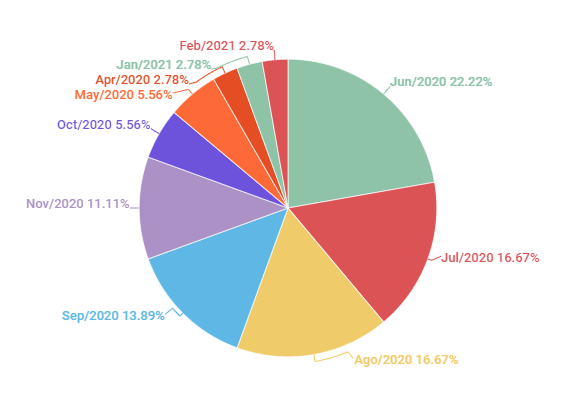

As shown in Graph 13 below, the periods with the highest case rates found were June, July and August 2020. It is not possible to be sure about the motivations for these attacks to have been carried out with greater intensity during these months, but it can be speculated that, in addition to social isolation, these are usually months of school and academic recess – which, while providing a greater number of online debates and conferences in the sciences, may also favor greater availability of free time, by the attackers, to seek such content. And, considering that municipal elections took place in November, it makes sense to suppose that there might be some correlation between the period of electoral campaigns and the high number of cases between September, November and October, although it is not possible to confirm this hypothesis at the moment.

10.About the sources: how many cases were collected in open letters, journalistic articles or articles in institutional news portals?

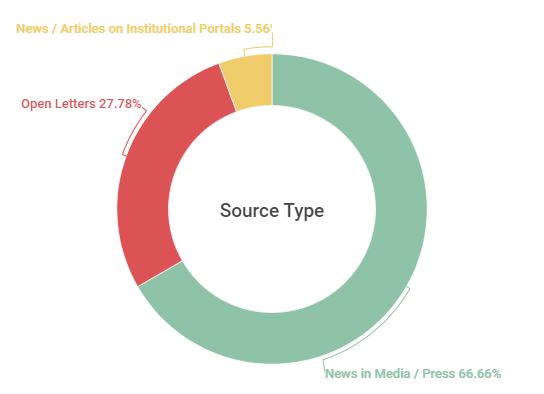

Inserting information about how many of the sources analyzed were open letters, journalistic articles or articles / videos in institutional news portals was considered important not only to highlight the methodological aspects described in section 2, but also to understand the position of civil society in relation to the theme.

As discussed in the Methodology section, documents such as disapproval notes from the affected institutions themselves were prioritized. When these did not exist or were not available, journalistic news was sought and, in their absence, articles or videos on portals of the entities promoting the events.

Although it is not possible to draw large conclusions because, for this article, only one document was collected (regardless of its type, whether journalistic news, disapproval note or article on portal), it is clear that, even prioritizing the registration of disapproval notes institutional, the highest percentage of documents was news in the media (66.67%). Notes published by the institutions themselves corresponded to 27.78% of the sources and, finally, articles or videos on institutional portals, with no open letters expressed on the topic, made up 5.56% of the documents (Graph 14).

11.Considerações finais

According to what was presented in section 5, the attack methods most used in the cases analyzed by the monitoring, in decreasing order, were the offensive images and / or terms, including symbols and terms associated with Nazism; nudity, pornography and sexual content; rape and death threats; noises and music; and provoking instabilities in the transmission of events. In at least 14% of the cases, the sources (notes, news, etc.) mention that the aggressors also shouted or wrote “Bolsonaro” and messages of support to the current Brazilian president. And, in at least 75% (27) of the cases, the sources also indicate that the attacks were in a group, with several users acting together – in only 8.33% (3) of them, the attack was individual, carried out by one or two isolated users, and in 16.67% (6) of them such information it does not exist, and it is not possible to say whether the attack was carried out in groups or in isolation.

Additionally, as presented in section 6 and its corresponding subsections, in addition to concluding that the greatest number of occurrences involved racist attacks and / or racial injury, it was also possible to infer that there was a great intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) between themes and attacks on vulnerable groups of different categories – such as black women – at the same time. This only reinforces the importance of discussing a more secure, democratic and plural digital environment for all social minorities that have been a recurrent target of aggressions, invasions and attempts to destabilize the network debate.

From the data observed in section 7, it was also possible to verify that, among the collected events, seminars, meetings, congresses and other types of academic virtual presentations were the most frequently affected, corresponding to 77.78% of the total. In addition, there was also a higher prevalence of cases that occurred on the Google Meet (20%) platform, and in smaller quantities on Zoom (14.29%), Instagram and Youtube (8.57%). Still in this section, it was possible to notice that, among the cases in which there was mention if the meetings were fully open, upon registration or closed, at least 50% were fully open and without the need for registration, and there was no such information in 18 cases (50%).

It is also worth noting that, as presented in section 9, the months of July (representing 22.22% of the cases), June and August (16.67% each), all of 2020, were the periods in which most of the attacks occurred.

The data shown in section 10, in turn, indicates that, even though the methodology prioritized the collection of institutional open letters, the news in the media were the main responsible for addressing the theme, causing 66.67% of the cases to have been analyzed using this type of source. Although it is not possible to conclude much with this information alone, it is possible to observe a certain trend in the media acting to denounce such aggressions even when the affected institutions do not issue notes of repudiation or do not make them public.

Finally, it is necessary to reiterate how important it was also to recover concepts previously worked on by other authors in a literature review that provided the introduction of ideas such as “Zoombombing”, “intersectionality” and the debate on the increase in hate crimes, attacks and invasions during the covid-19 pandemic. With the monitoring and analysis resulting from it, it was possible to reach the conclusions presented in the paragraphs above (even though it is necessary to note that it refers to a small sample field of cases, so there are limitations of the conclusions and inferences made), but only with its association with the bibliographic review methodology was possible to conclude that there are different types of attacks, methods, locations, platforms, targets and victims not only due to the inequalities and dilemmas present on the Internet, but also due to structural issues that have been out of it for a long time, and that when events and dynamics were transported, which until then were present in the digital domain, in a period of instability and isolation, are reinforced and brought to the surface in an intense and recurring way.

Bibliography

Alves, S. (2020). Além do racismo, reconhecimento facial erra mais em pessoas trans. UOL Notícias / Tilt. Available at: <https://www.uol.com.br/tilt/noticias/redacao/2021/02/14/nao-e-so-racismo-reconhecimento-facial-tambem-erra-mais-em-pessoas-trans.htm>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Amnesty (2017). Amnesty reveals alarming impact of online abuse against women. Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/11/amnesty-reveals-alarming-impact-of-online-abuse-against-women/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Amorim, L. (2020). Seminário sobre consciência negra termina com ataques racistas em Araquari. Joinville: Ndmais [Online]. Available at: <https://ndmais.com.br/seguranca/policia/seminario-sobre-consciencia-negra-termina-com-ataques-racistas-em-araquari/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Batty, D. (2020). Harassment fears as students post extreme pornography in online lectures. The Guardian [Online]. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/apr/22/students-zoombomb-online-lectures-with-extreme-pornography>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Bertolozzi, T. B. (2021). It wasn’t just Twitter: remember Trump bans on Twitch. São Paulo: Medium [Online]. Available at: <https://thaylabb.medium.com/it-wasnt-just-twitter-remember-trump-bans-on-twitch-51e1f461b3e6>. Accessed: 21 mar. 2021.

Caldas, J. Hackers invadem reunião virtual do Conselho de Direitos Humanos de SC com ataques racistas e homofóbicos. Santa Catarina: G1 [Online]. Available at: <https://g1.globo.com/sc/santa-catarina/noticia/2020/11/20/hackers-invadem-reuniao-virtual-do-conselho-de-direitos-humanos-de-sc-com-ataques-racistas-e-homofobicos.ghtml>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Carta Capital; Estadão (2020). Hackers bolsonaristas invadem lives de acadêmicos. Carta Capital; Estadão Conteúdo [Online]. Available at: <https://www.cartacapital.com.br/sociedade/hackers-bolsonaristas-invadem-lives-de-academicos/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Casaletti, D. (2020). Lives interrompidas: artistas relatam ataques de hackers, perda de seguidores e instabilidades. Estadão [Online]. Available at: <https://cultura.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,lives-interrompidas-artistas-relatam-ataques-de-hackers-perda-de-seguidores-e-instabilidades,70003516798>. Accessed; 27 feb. 2021.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Gender, black feminism, and black political economy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 568 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1177/000271620056800105. S2CID 146255922.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal forum, vol. 1989, issue 1. Available at: <https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Dias, T. (2020). Crimes explodem no Facebook, Youtube, Twitter e Instagram durante a pandemia. The Intercept Brasil [Online]. Available at: <https://theintercept.com/2020/08/24/odio-pornografia-infantil-explodem-twitter-facebook-instagram-youtube-pandemia/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Estadão Conteúdo; IstoÉ (2020). Em Joinville, primeira vereadora negra é alvo de ataque racista. IstoÉ [Online]. Availabel at: <https://www.istoedinheiro.com.br/em-joinville-primeira-vereadora-negra-e-alvo-de-ataque-racista/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Folha de S. Paulo (2020). Anitta se posiciona sobre ataques racistas que Ludmilla vem sofrendo dos seus fãs. São Paulo: Folha de S. Paulo. Available at: <https://f5.folha.uol.com.br/celebridades/2020/06/anitta-se-posiciona-sobre-ataques-racistas-que-ludmilla-vem-sofrendo-dos-seus-fas.shtml>. Accessed: 20 mar. 2021.

Ging, D.; Siapera, E. (2018). Special issue on online misogyny. Feminist Media Studies, 18:4, 515-524. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447345>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021. DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2018.1447345

Godoy, M. (2020). Lives de acadêmicos viram alvo de hackers. O Estado de S. Paulo [Online]. Available at: <https://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,lives-de-academicos-viram-alvo-de-hackers,70003435480>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Guedes, E. (2021). Reconhecimento Facial e suas intersecções com a divesidade de gênero, raça e território. Coding Rights. Medium [Online]. Available at: <https://medium.com/codingrights/from-devices-to-bodies-reconhecimento-facial-e-suas-intersecções-com-a-divesidade-de-gênero-raça-3b7d9b89805b>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Ifto (2020). Nota de Repúdio. Available at: <ifto.edu.br/noticias/nota-de-repudio.2>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

iG Último Segundo (2020). Hackers invadem transmissão ao vivo de pré-candidata do PSOL. iG Último Segundo [Online]. Available at: <https://ultimosegundo.ig.com.br/politica/2020-08-21/hackers-invadem-transmissao-ao-vivo-de-pre-candidata-do-psol.html>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

iG Último Segundo. 2020.

InternetLab (2020). MonitorA: discurso de ódio contra candidatas nas eleições de 2020. Available at: <https://www.internetlab.org.br/pt/desigualdades-e-identidades/internetlab-azmina-discurso-de-odio-contra-candidatas-nas-eleicoes-de-2020/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Jornal Correio do Amanhã (2020). Live com Intelectuais negros sofre ataque racista de hackers. Available at: <https://www.jornalcorreiodamanha.com.br/sociedade/2757-live-com-intelectuais-negros-sofre-ataque-racista-de-hackers>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Kalil, I. O. (coord.) (2018). Quem são e no que acreditam os eleitores de Jair Bolsonaro. Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo. Available at: < https://www.fespsp.org.br/upload/usersfiles/2018/Relat%C3%B3rio%20para%20Site%20FESPSP.pdf>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Keum, B. T.; Miller, M. J. (2018). Racism on the Internet: Conceptualization and Recommendations for Research. Psychology of Violence. Advance online publication. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325636856_Racism_on_the_Internet_Conceptualization_and_Recommendations_for_Research>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021. DOI: DOI: 10.1037/vio00002Lima, M. 01.

Khan, N.; Brohi, S. N.; Zaman, N. (2020). Ten Deadly Cyber Security Threats Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Preprint. Research Gate. Available at: <researchgate.net/publication/341324576_Ten_Deadly_Cyber_Security_Threats_Amid_COVID-19_Pandemic>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021. DOI: 10.36227/techrxiv.12278792.v1.

Lima, M.; Milanezi, J. Venturini, A. C.; Bertolozzi, T. B.; Sousa, C. J. Barbosa, H. N. (2020). Desigualdades Raciais e Covid-19: o que a pandemia encontra no Brasil?. Available at: < https://cebrap.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Afro_Informativo-1_final_-2.pdf>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Lopes, N. (2021). Veterinária negra tem palestra online interrompida por sons de macacos. São Paulo: UOL Notícias. Available at: <https://noticias.uol.com.br/cotidiano/ultimas-noticias/2021/03/20/veterinaria-negra-tem-palestra-online-invadida-com-sons-de-primatas.htm>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

MaRIas (2020). Nota de repúdio – Invasão de encontro virtual do MaRIas. Available at: <143.107.26.205/documentos/Nota_repudio-encontroMaRIas.pdf>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Moura, R. (2020). Grupo extremista ataca seminário virtual do IFPR. Plural. Available at: <https://www.plural.jor.br/noticias/vizinhanca/grupo-extremista-ataca-seminario-virtual-do-ifpr/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Mouton, F.; De Coning, A. (2020). COVID-19: Impact on the Cyber Security Threat Landscape. Research Gate. Preprint of Article Project: Social Engineering: Defining the field from Both an Attack and Defence Perspective. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340066124_COVID-19_Impact_on_the_Cyber_Security_Threat_Landscape>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27433.52325.

O Globo; Yahoo! Notícias Brasil (2020). Teresa Cristina ameaça parar de fazer lives após sucessivos ataques de hackers. Available at: <https://br.noticias.yahoo.com/teresa-cristina-ameaça-parar-fazer-010247906.html>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

O Liberal (2020). UFPA repudia ataques feitos contra programações virtuais da instituição. O Liberal [Online]. Availabel at: <https://www.oliberal.com/para/ufpa-repudia-ataques-feitos-contra-programacoes-virtuais-da-instituicao-1.298442>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Schuster, K. (2021). COVID pandemic can make teens easy targets for radicalization. Deutsche Welle [Online]. Available at: <https://www.dw.com/en/covid-pandemic-can-make-teens-easy-targets-for-radicalization/a-56469580>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Senra, R. (2020). Invasão com suásticas e vídeos de decapitação interrompe reunião virtual de mulheres sobre racismo. BBC News Brasil. Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-53030511>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Sinasefe Ifes (2020). Pornografia e até ameaças em invasões a lives do Ifes. Available at: <https://www.sinasefeifes.org.br/pornografia-e-ate-ameacas-em-invasoes-a-lives-do-ifes/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

UFSM (2020). Nota da UFSM sobre incidente em aula aberta. Portal UFSM [Online]. Available at: <https://www.ufsm.br/2020/07/07/nota-da-ufsm-sobre-incidente-em-aula-aberta/>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Unicamp (2020). Reitoria divulga nota de repúdio ao ataque cibernético racista. Portal Unicamp [Online]. Availabel at: <https://www.unicamp.br/unicamp/noticias/2020/06/09/reitoria-divulga-nota-de-repudio-ao-ataque-cibernetico-racista>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Universa (2020). Thelma comenta ataques racistas em live: ‘Chegou ao limite para mim’. São Paulo: Universa / UOL. Available at: <https://www.uol.com.br/universa/noticias/redacao/2020/05/28/thelma-comenta-ataques-racistas-em-live-chegou-ao-limite-para-mim>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021.

Young, S. (2020). Zoombombing Your Toddler: User Experience and the Communication of Zoom’s Privacy Crisis. Journal of Business and Technical Communication. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344434373_Zoombombing_Your_Toddler_User_Experience_and_the_Communication_of_Zoom%27s_Privacy_Crisis>. Accessed: 27 feb. 2021. DOI: 10.1177/1050651920959201.